By Russ:

During the decade of the 1970s I started to become aware of a new music genre that was emerging.. Heavy on the bass, it was an electrifying rock-influenced musical hybrid of ska, R&B and jazz. This genre would propel a humble and spiritual Jamaican singer-songwriter into becoming a global figure in pop culture.

Back then, I was working for an environmental consultant company and, from the cubicle of a young engineer next to me, I started to hear about this music. He said it was Bob Marley. I listened to it and was blown away. This is one of the first songs I heard:

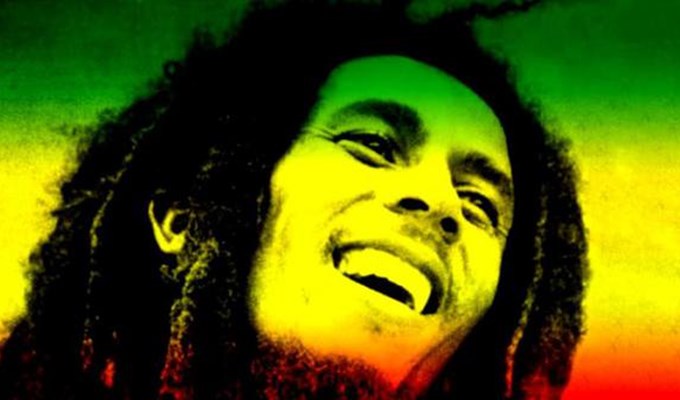

Considered one of the pioneers of the reggae movement, Bob Marley fused elements of ska and rocksteady, and came up with a very catchy, soulful sound. He became renowned for his distinctive vocals and performance persona. His contribution to music irrefutably increased the visibility of Jamaican music worldwide.

Over the course of his career, Marley also became known as a Rastafarian icon, and he infused his music with a sense of spirituality. He also supported the legalization of cannabis, and advocated for Pan-Africanism.

Considered a global symbol of Jamaican culture and identity, Marley was controversial in his outspoken support for democratic social reforms. In 1976, he survived an assassination attempt in his home, which was thought to be politically motivated.

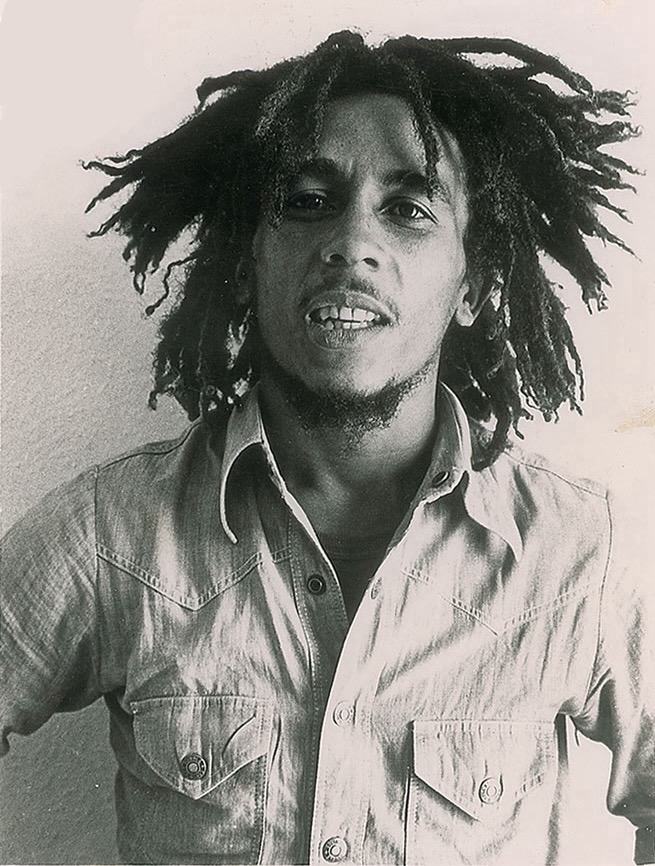

Bob Marley

Born February 6, 1945, Nine Miles, St. Ann, Jamaica

Died (age 36 of Cancer) May 11, 1981, Miami, Florida, U.S.

VIDEOS

1977 / I Shot The Sheriff

1977 / No Woman No Cry

Buffalo Soldier

Could You Be Loved

Early life and career

Bob Marley was born February 6, 1945 as Robert Nesta Marley in rural Rhoden Hall in the Parish of St. Ann, Jamaica. His mother was a Jamaican teenager, Cedella Malcolm, the black daughter of a local custos (honored civic official). His father, Norval Sinclair Marley was a white middle-aged captain in the West Indian regiment of the British Army.

Marley’s maternal grandfather was a prosperous farmer but also a bush doctor adept at the mysticism-steeped herbal healing that guaranteed respect in Jamaica’s remote hill country.

As a child, Marley was known for his shy aloofness, his startling stare, and his penchant for palm reading.

Virtually kidnapped by his absentee father (who had been disinherited by his own prominent family for marrying a Black woman), the preadolescent Marley was taken to live with an elderly woman in Kingston until a family friend rediscovered the boy by chance and returned him to the village of Nine Miles.

Marley’s parents separated when he was six, and soon thereafter, he moved with his mother to Kingston, joining the wave of rural immigrants that flooded the capital during the 1950s and 1960s.

They settled in Trench Town, a west Kingston slum named for the sewer that ran through it. There, Marley shared quarters with a boy his age named “Bunny” Neville O’Riley Livingston. The two made music together, making a guitar from bamboo, sardine cans, and electrical wire and learning harmonies from a local singer, Joe Higgs.

Like a number of their generation, young Marley and Bunny listened to radio from New Orleans; and they embraced the sounds of rhythm and blues, combining them with pieces of their own musical style, producing a (then) new music called ska.

In the early 1960s, while a schoolboy he was encouraged by his mother to take up a craft serving an apprenticeship as a welder (along with fellow aspiring singer Desmond Dekker). During that time, Marley was exposed to the languid jazz-inflected shuffle-beat rhythms of ska, a Jamaican amalgam of American rhythm and blues and Jamaican mento (folk-calypso) strains then catching on commercially. Marley soon abandoned an apprenticeship as a welder to devote himself to music.

By his early teens Marley was back in West Kingston, living in government-subsidized housing in Trench Town, a desperately poor area often compared to an open sewer.

Marley was a fan of Fats Domino, the Moonglows, and pop singer Ricky Nelson, but, when his big chance came in 1961 to record with producer Leslie Kong, he cut “Judge Not,” a peppy ballad he had written that was derived from rural maxims learned from his grandfather.

His first song – “Judge Not”

.

1962 / “One Cup Of Coffee”

Among his other early tracks was “One Cup of Coffee” (a rendition of a 1961 hit by Texas country crooner Claude Gray), issued in 1963 in England on Chris Blackwell’s Anglo-Jamaican Island Records label.

Formation of the Wailers

Marley formed a vocal group in Trench Town with friends who would later be known as Peter Tosh (original name Winston Hubert MacIntosh) and Bunny Wailer (original name Neville O’Reilly Livingston). Tosh played guitar and did vocal harmonies. Wailer was a percussionist with vocal harmonies.

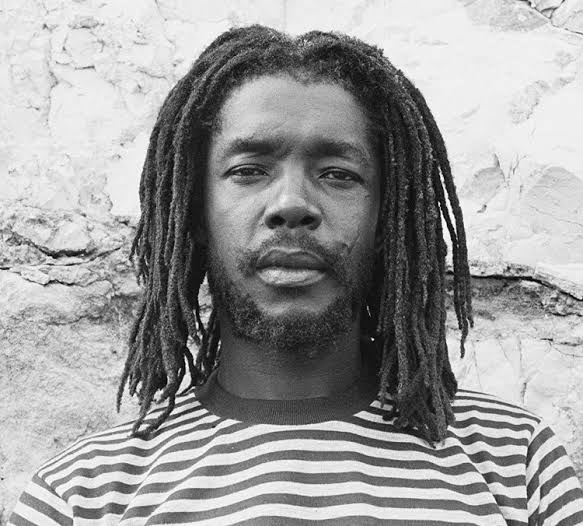

BUNNY WAILER

The trio, which named itself the Wailers (because, as Marley stated, “We started out crying”), received vocal coaching by noted singer Joe Higgs. Later they were joined by vocalist Junior Braithwaite and backup singers Beverly Kelso and Cherry Green.

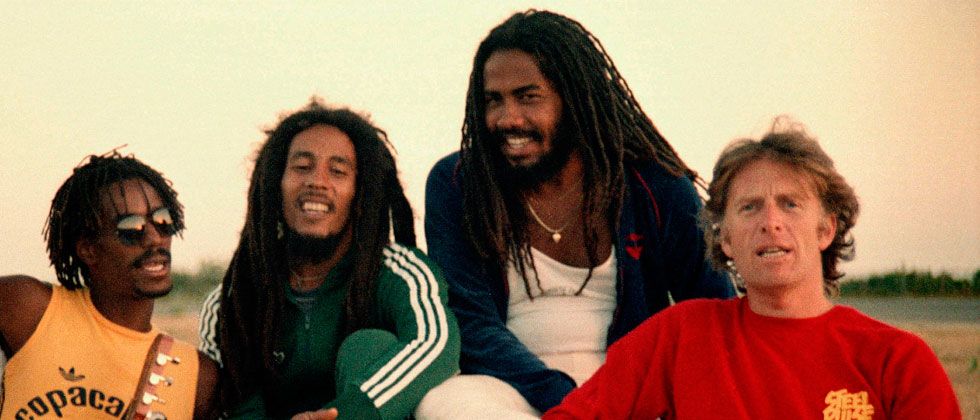

Bob Marley with the Wailers: (from left) Bunny Wailer, Marley, Carlton Barrett, Peter Tosh, and Aston (“Family Man”) Barrett.

1963 / Simmer Down

In December 1963 the Wailers entered Coxsone Dodd’s Studio One facilities to cut “Simmer Down,” a song by Marley that he had used to win a talent contest in Kingston.

.

Unlike the playful Mento music that drifted from the Jamaican porches of local tourist hotels, and unlike the Pop and R&B that was waving into Jamaica from late night American radio stations, the Wailers’ song “Simmer Down” was an urgent anthem from the shantytown precincts of the Kingston underclass.

A huge overnight smash, “Simmer Down” played an important role in recasting the agenda for stardom in Jamaican music circles.

No longer did one have to parrot the stylings of overseas entertainers; it was possible to write raw, uncompromising songs for and about your own backyard – the disenfranchised, poverty-stricken West Indians.

This bold stance transformed both Marley and his island nation, engendering the urban poor with a pride that would become a pronounced source of identity (and a catalyst for class-related tension) in Jamaican culture.

The Role of Rastafari, and international fame

In 1963 his mother moved to Delaware; Marley followed with a lengthy visit in 1966, working jobs for Chrysler and Dupont. Yet his heart lay back home, where his new wife, Jamaican Rita Anderson, and his old passion for the island’s music remained.

When he returned home in 1967, Marley converted from Christianity to Rastafarianism, a creed popular among the impoverished people of the Caribbean, who worshipped the late Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie I as the African redeemer foretold in popular quasi-biblical prophecy.

Thus began the mature stage of his musical career. He reunited with Bunny and Peter Tosh, and as The Wailers they started their record label, “Wail ‘N Soul ‘M”.

The Wailers recorded more than 30 singles in the mid-1960s, reflecting and sometimes leading the evolution of reggae from mento to ska to rock steady.

They abandoned the rude-boy philosophy for the spirituality of Rastafarian beliefs slowing their music under the new “rock steady” influence. Although the Wailers began to fit together as a group, they did not find success beyond Jamaica.

The Wailers did well in Jamaica during the mid-1960s with their ska records, even during Marley’s sojourn to Delaware in 1966 to visit his relocated mother and find temporary work. Reggae material created in 1969–71 with producer Lee Perry increased the contemporary stature of the Wailers.

Once the Wailers signed in 1972 with the Island label, which had just become internationally recognized, and released Catch a Fire (the first reggae album conceived as more than a mere singles compilation), their uniquely rock-contoured reggae gained global audience.

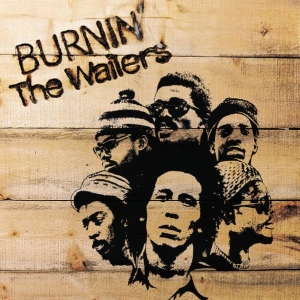

6th Studio Album – BURNIN’

Burnin’ was the sixth album by Jamaican reggae group the Wailers (also known as “Bob Marley and the Wailers”), released in October 1973.

Burnin’ opens with one of The Wailers best known songs, the call to action “Get Up, Stand Up” and includes a more confrontational and militant tone than previous records.

Burnin’ was written by all three members and recorded and produced by the Wailers in Jamaica, contemporaneously with tracks from the Catch a Fire album with further recording, mixing and completion while on the Catch a Fire tour in London. It contains the song “I Shot the Sheriff“.

This was the last album before Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer decided to pursue separate solo careers, while continuing their local releases through their company Tuff Gong Records. A commercial and critical success in the United States, Burnin’ was certified Gold and later added to the National Recording Registry, with the Library of Congress deeming it historically and culturally significant.

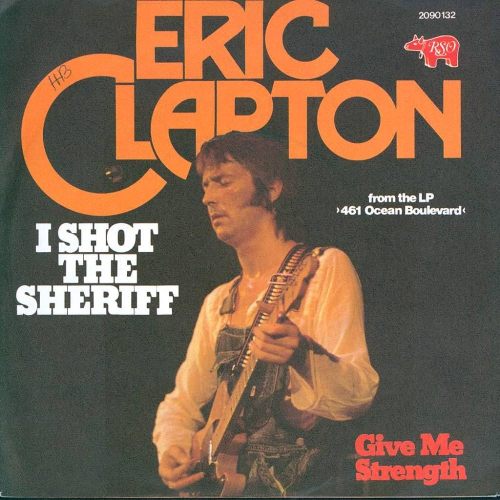

1973 / I Shot The Sheriff

I Shot the Sheriff is a song written and composed by Bob Marley and released in 1973 as Track #3 on the Burnin’ album.

I shot the sheriff But I didn’t shoot no deputy, oh no! Oh! I shot the sheriff But I didn’t shoot no deputy, ooh, ooh, oo-ooh.) Yeah! All around in my home town, They’re tryin’ to track me down; They say they want to bring me in guilty For the killing of a deputy, For the life of a deputy. But I say: Oh, now, now. Oh! (I shot the sheriff.) – the sheriff. (But I swear it was in self-defence.) Oh, no! (Ooh, ooh, oo-oh) Yeah! I say: I shot the sheriff – Oh, Lord! – (And they say it is a capital offence.) Yeah! (Ooh, ooh, oo-oh) Yeah! Sheriff John Brown always hated me, For what, I don’t know: Every time I plant a seed, He said kill it before it grow – He said kill them before they grow. And so: Read it in the news: (I shot the sheriff.) Oh, Lord! (But I swear it was in self-defence.) Where was the deputy? (Oo-oo-oh) I say: I shot the sheriff, But I swear it was in self-defence. (Oo-oh) Yeah! Freedom came my way one day And I started out of town, yeah! All of a sudden I saw sheriff John Brown Aiming to shoot me down, So I shot – I shot – I shot him down and I say: If I am guilty I will pay. (I shot the sheriff,) But I say (But I didn’t shoot no deputy), I didn’t shoot no deputy (oh, no-oh), oh no! (I shot the sheriff.) I did! But I didn’t shoot no deputy. Oh! (Oo-oo-ooh) Reflexes had got the better of me And what is to be must be: Every day the bucket a-go a well, One day the bottom a-go drop out, One day the bottom a-go drop out. I say: I – I – I – I shot the sheriff. Lord, I didn’t shot the deputy. Yeah! I – I (shot the sheriff) – But I didn’t shoot no deputy, yeah! No, yeah!

A few months before the release of “I Shot the Sheriff”, Marley and his group, the Wailers, were abandoned in London by their NY label JAD, in the cold and without a penny (or even their passport!). Bob knocked on the door of Chris Blackwell, an Anglo-Jamaican playboy, founder of Island Records.

In 1974, Eric Clapton’s version of the Wailers’ “I Shot the Sheriff” spread the recognition of Marley’s music and ensuing fame like pouring water on a grease fire.

.

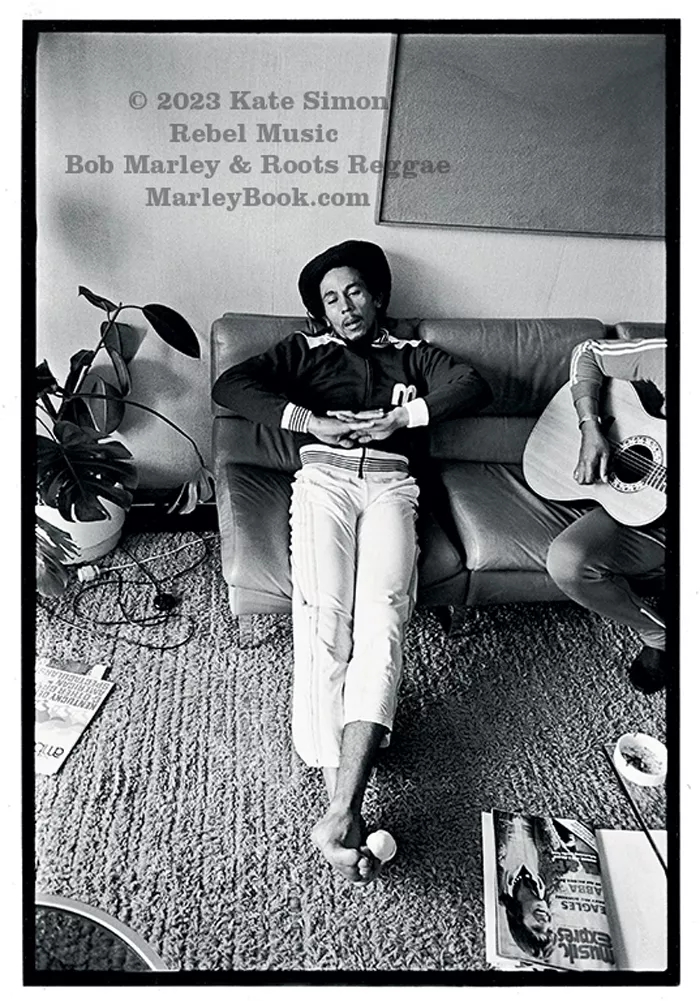

Meanwhile, Marley continued to guide the very skilled and talented Wailers band through a series of incredible recording projects. Several topical and powerful vinyl LP albums were produced featuring eloquent songs like “No Woman No Cry,” “Exodus,” “Could You Be Loved,” “Coming in from the Cold,” “Jamming,” and “Redemption Song,”

Carried by Marley’s reedy tenor voice, his songs were public expressions of personal truths—eloquent in their uncommon mesh of rhythm and blues, rock, and venturesome reggae forms and electrifying in their narrative might. Making music that transcended all its stylistic roots, Marley fashioned an impassioned body of work that was sui generis (unique / of it’s own kind).

Fame of the Wailers band earned the charismatic Marley a superstar status, which gradually led to the dissolution of the original triumvirate of Marley, Tosh and Wailer around early 1974.

Although Peter Tosh would enjoy a distinguished solo career before his murder in 1987, many of his best solo albums (such as Equal Rights [1977]) were underappreciated, as was Bunny Wailer’s excellent solo album Blackheart Man (1976).

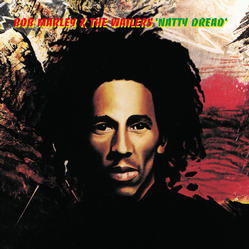

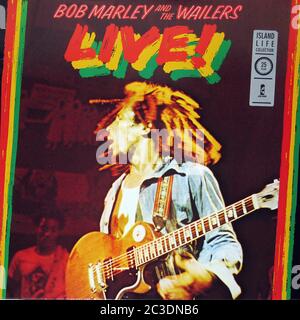

Marley’s landmark albums:

included Natty Dread (1974), Live! (1975), Rastaman Vibration (1976), Exodus (1977), Kaya (1978), Uprising (1980), and the posthumous Confrontation (1983).

By this point Marley was also being backed by a trio of female vocalists including his wife, Rita Marley (née Alfarita Constania Anderson). Rita Marley would later achieve her own recording success, as would many of the couple’s children, especially together as the group Ziggy Marley and the Melody Makers, led by Marley’s eldest son.

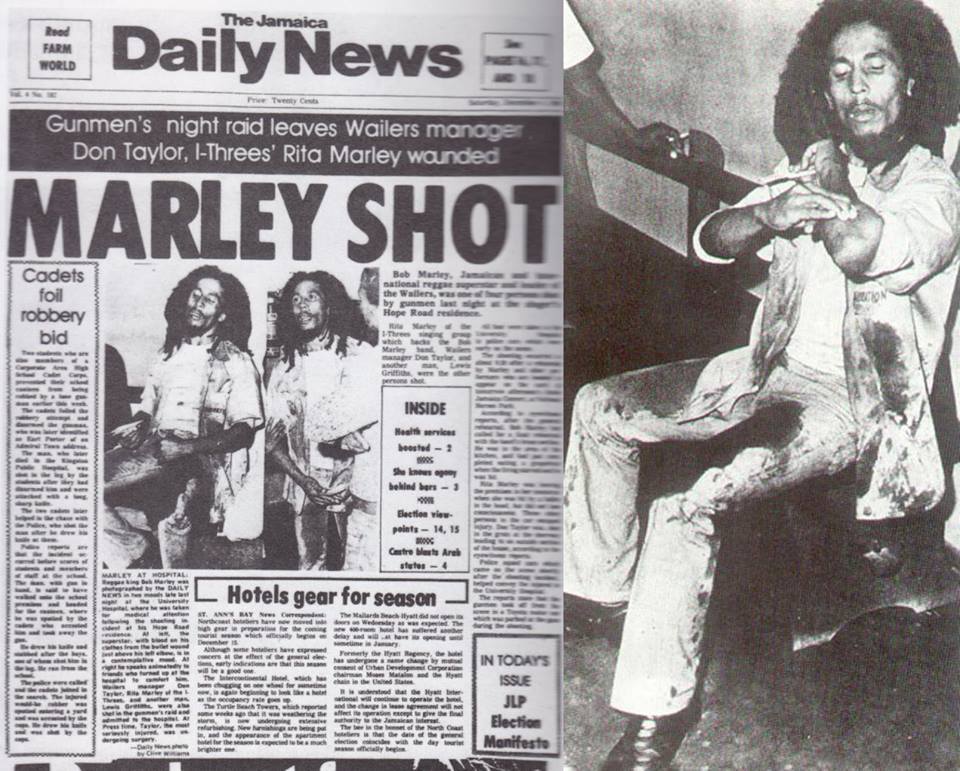

Marley’s political involvement and Attempted Assassination

Marley loomed large as a political figure and in 1976 survived what was believed to have been a politically motivated assassination attempt. The Smile Jamaica Concert—at which Marley and the Wailers were scheduled to perform on December 5, 1976, and which was initially framed as an apolitical celebration of community—came to be widely viewed as an endorsement of Michael Manley, the incumbent prime minister of the People’s National Party. Manley sought to capitalize on that perception by following the announcement of the concert with a call for legislative elections.

Two days before the concert, a group of gunmen, perhaps seeking to punish Marley for his (supposed) support of Manley, broke into Marley’s home and wounded Rita Marley, Bob Marley’s manager (Don Taylor), an employee of the band, and Marley himself.

Marley’s chest was grazed and his arm was struck with a bullet, but he survived. He recovered and with The Wailers played a 90-minute set for the 80,000 people in attendance.

Marley Flees Jamaica

Shortly after performing the concert, Marley fled Jamaica, first to the Bahamas and then to London, UK, where he lived in exile for a time.

Record Producer Chris Blackwell recalls, with pinpoint vividness, the moment Bob Marley walked into his London office. It was 1972, and Marley, along with fellow Wailers bandmates Peter Tosh and Bunny (Livingston) Wailer, found themselves stranded after being invited to go to Sweden to do music for a film that had fallen through. The musicians, down and out, had just enough money to get from Stockholm to England. With no way to get home to Jamaica, their ultimate destination, they connected with Blackwell through a friend and requested a meeting.

Blackwell, then a 35-year-old budding music and entertainment mogul, was interested, of course, in meeting the young musicians. As the founder of Island Records, which he started at age 22, Blackwell had a huge hand in popularizing Jamaican music that eventually became known as ska. He’d even released some of the Wailers’ early records, including “Bend Down Low,” as well as their first record, “Judge Not,” which was produced by Leslie Kong, in Jamaica.

But he’d never met the lads — and didn’t exactly know what to expect. “They all struck me as special,” recalled Blackwell, who was working with Toots and the Maytals, the Jamaican group that brought the word “reggae” to the world with their 1968 single “Do the Reggay.” “I got this call to say they were stranded — yet when they came into my office, they came in a way like princes: They had a strong personality, a strong sense of self. They were impressive. I was immediately enamored with them.” Call it happenstance, or even serendipity, but the meeting couldn’t have come at a better time for Blackwell, and for the Wailers. Blackwell had lost his main Jamaican reggae artist, Jimmy Cliff, who had decided to leave Island Records to sign with EMI just a week before.

“At that period and time, I was very involved with rock music and not so involved in the day-to-day Jamaican music anymore,” Blackwell said. The Wailers needed Blackwell, and Blackwell needed the Wailers.

The rest, as they say, is history — beautiful, soulful history. A few months after that chance meeting, Blackwell found himself in Jamaica and in a studio with the Wailers, who played him Catch a Fire, their 1973 LP and first album released by Blackwell’s Island Records. It was the start of a lifelong friendship, as Blackwell would co-produce virtually all of Marley’s classic ’70s albums and contribute to his appeal to a worldwide audience.

“My experience with him was nothing but great,” reflected Blackwell, now 79. “We never had an argument, never had a misunderstanding. He always kept his word on everything. He led by example. He was a natural leader. Bob was always the first one on the bus. That was totally unique. I’d never seen that before. He was very understated and didn’t make a lot of noise. He just had that kind of aura.”

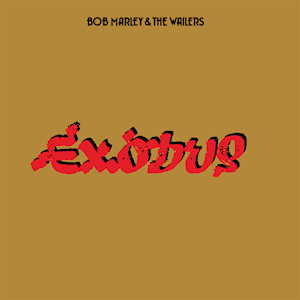

They recorded Exodus. This album would be hailed by Time magazine as the most important album of the 20th century, “a political and cultural nexus, drawing inspiration from the Third World and then giving voice to it the world over.”

Exodus thematically moves away from cryptic story-telling; instead it revolves around themes of change, religious politics, and sexuality. The album is split into two halves: the first half revolves around religious politics, while the second half is focused on themes of making love and keeping faith.

The album was a success both critically and commercially; it received gold certifications in the US, UK and Canada, and was the album that propelled Marley to international stardom.

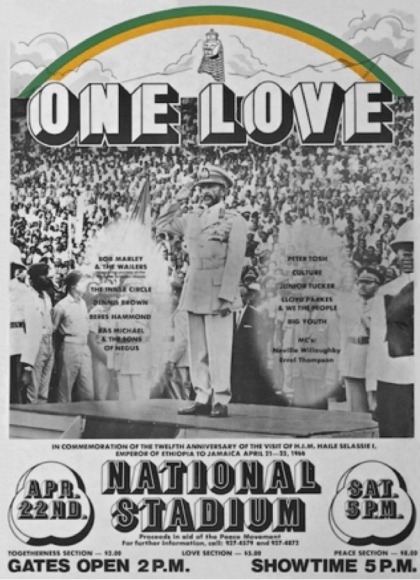

The One Love Peace Concert

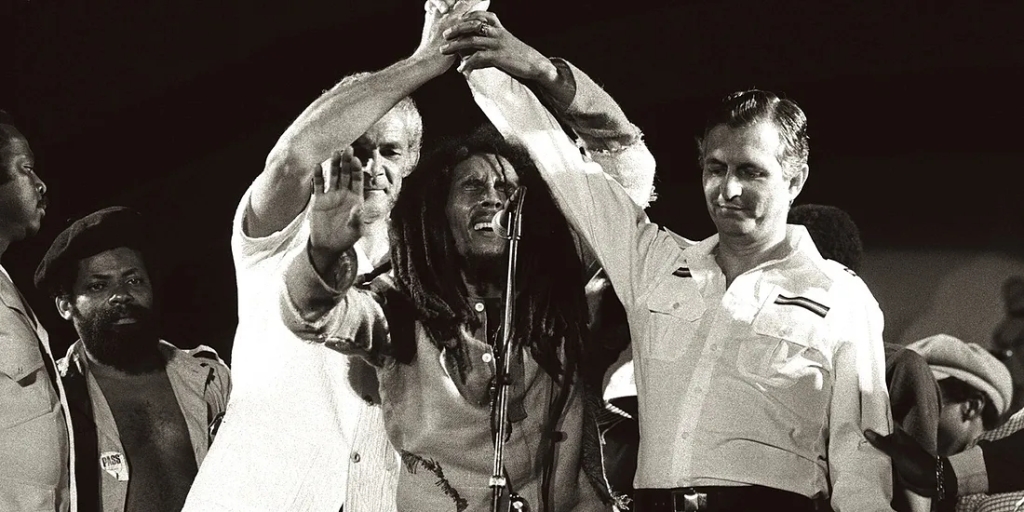

In 1978, according to some observers, Jamaica was on the brink of civil war, and Marley’s attempt to broker a truce between the country’s warring political factions led in April of that year to his headlining the One Love Peace Concert.

The One Love Peace Concert brought together 16 of Reggae’s biggest acts, and was dubbed by the media as the “Third World Woodstock“, “Bob Marley plays for Peace” and simply, “Bob Marley Is Back.” The concert attracted more than 32,000 spectators with the proceeds of the show going towards “much needed sanitary facilities and housing for the sufferahs in West Kingston.” The concert was kicked off at exactly 5:00 PM with a message from Asfa Wossen, the crown prince of Ethiopia, praising the concert organizers’ efforts to restore peace in Jamaica. This introduction to the event is important in illustrating the growing prevalence of the Rastafari movement in everyday Jamaican culture. The concert was divided into two halves, with the first half devoted to showcasing some of Reggae’s newer talent, and the second half devoted to the more established artists.

Jacob Miller energetically launched the second half of the concert, during which time Edward Seaga and Michael Manley got to their seats. The highlight of Miller’s performance came when he “leaped onto the field with lighted spliff herb and offered it to a police man, donned the lawman’s helmet, jumped back onto the stage and continued the number as he paraded the herb.” Alternatively, Peter Tosh took the opportunity during his performance to berate the two political leaders sitting directly in front of him for their positions against legalizing marijuana. His set lasted 66 minutes, and Tosh spent almost half of that time denouncing the problems prevalent in society.

At around 12:30 AM, Bob Marley took the stage to perform some of his biggest hits. The climax came during his performance of Jammin’ when he called both Michael Manley and Edward Seaga to the stage, and in a symbolic gesture, the three held up their hands together to signify their unity.

Edward Seaga of the Jamaica Labour Party would become prime minister in 1980.

Marley’s sociopolitical clout also earned him an invitation to perform in 1980 at the ceremonies celebrating majority rule and internationally recognized independence for Zimbabwe.

Legacy

In April 1981 the Jamaican government awarded Marley the Order of Merit. A month later he died of cancer. Under the nail of his big toe, he did not know that he had melanoma..

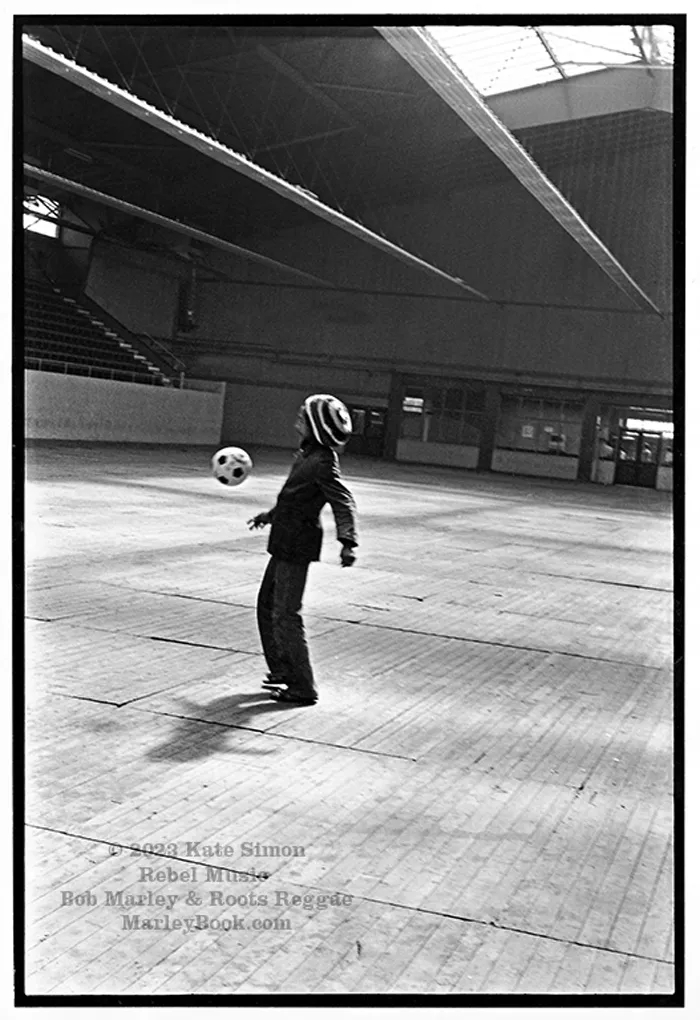

Chris Blackwell re. Marley’s Death

“The whole thing of Bob passing was just really a tragedy, a disgrace in a sense,” Blackwell lamented. “Nobody, absolutely nobody — from he himself, people close to him, to those who worked with him after that period, including myself — never mentioned anything to him about having regular checkups to see if there were any negative effects from the [soccer] accident he had on his toe. We did know that he was advised to have it amputated, and he didn’t want to do that because he loved soccer — 98 percent as much as he loved music. The thought that if he had his toe cut off he would no longer be able to play soccer in the same way, without the agility with his foot.

“It’s a disgrace that all of us involved were not on him all the time to make sure he had checkups, and that really what happened. Nobody did anything, and when it happened it was too late, had spread too much, and there was nothing that could be done.”

The Legend Album

Although his songs were some of the best-liked and most critically acclaimed music in the popular canon, Marley is far more renowned in death than he had been in life. Legend (1984), a retrospective of his work.

This would become the best-selling reggae album ever, with international sales of more than 12 million copies.

BINGE SECTION

Bunny Wailer

Neville O’Riley Livingston (10 April 1947 – 2 March 2021), known professionally as Bunny Wailer, was a Jamaican singer-songwriter and percussionist. He was an original member of The Wailers along with Bob Marley and Peter Tosh. A three-time Grammy Award winner, he is considered one of the longtime standard-bearers of reggae music.

Bob Marley – Live Santa Barbara 1979

BOB MARLEY Live in Santa Barbara 1979 FULL CONCERT

Bob Marley: One Love – Official Trailer (2024 Movie)

–oo–